Half the confusion in the world comes from not knowing how little we need.

Richard E. Byrd

The French philosopher Jean Beaudrillard proposes that reversibility is the basis, the guarantor of human agency, that all our worldly concerns and engagements are proportionate to reversibility, that we are drawn to, engaged by situations where an outcome or expectation need not necessarily occur. Mechanical cause and effect or anything predetermined simply cannot compete with the excitement generated by contingency that animates, for example, financial markets or sporting events.

In 1971 John Lennon (dead at 42 in 1980) recorded the song “Imagine.” Eight years later, Bob Marley (dead at 36 in 1981) recorded “There’s So Much Trouble in the World.”

In answer to the troubles that were plaguing the world, Lennon was trying to imagine a new world order, one that Marley characterized as “no care for you no care for me.”

Where the Marley lyric falls short is in its lack of breadth. It’s not only “no care for you no care for me” but no care for the planet that is now on the endangered list. To quote Bill Maher in a rare moment of eloquence: “we eat shit, we breathe shit.”

The data points are no longer disputable: The world is over-heating, our erstwhile good air has been compromised by ozone and particulate matter, there’s a plastic cesspool the size of France floating (farting) in the Pacific, and “the water line is rising and all we do is stand there” on the corner watching the erstwhile good earth being turned into an open sewer. All in the name of consumption, the guarantor of happiness, so we are told as soon as we draw our first breath. But despite the science and the proliferation of “save the planet” initiatives, the Greens are losing out to the Browns (the skatamakers) because corporations, and not governments, write the rules.

At the top of the “no care” list – our elected leaders come a distant second – is the corporation, likened, by Joel Bakan, to a psychopath in its cold-blooded behaviour. In his book (The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power), the author describes the corporate entity, whose tentacles are everywhere, whose appetite is insatiable, as rapacious and immoral in pursuit of lucre.

During the 2009 financial meltdown, the Canadian government bailed out Chrysler with a 1.2 billion dollar tax-payer funded loan. Shortly thereafter, Chrysler reincorporated as Chrysler Fiat, which earned 4.3 billion in 2017. Since the old non-performing Chrysler received the loan, the Canadian government was unable to recuperate it, and (including accrued compounded interest) had to write off a 2.6 billion dollar loss. Now we all know that the law that allowed old Chrysler to finance the new Chrysler wasn’t drafted by the shoemaker or the candlestick maker. The corporation wrote the law specific to its interests, lobbied (paid off) the government to enact it, thus legalizing an act of grand theft against the Canadian taxpayer. That the fate of the planet is in the hands of the world’s most powerful (immoral) corporations is not an exaggeration but a numbers backed fact that should worry us all.

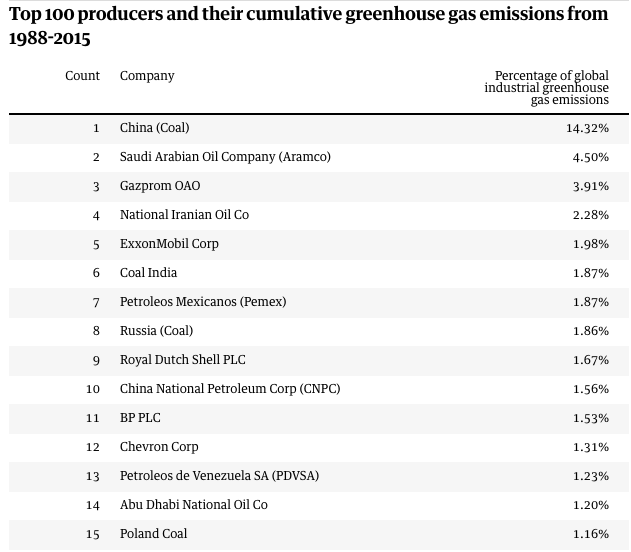

The Guardian reports that 100 companies are responsible for 71`% of the world’s global emissions.

Corporatism thrives, feasts on consumption, the algorithm that is inexorably rendering the earth uninhabitable. Most experts on both sides of the debate now agree that ocean temperatures are rising, fish stocks are depleting, the coral reef is on life support, 10% of all the earth’s children suffer in varying degrees from asthma, while the life expectancy curve is flattening out despite medical advances in all disciplines. Why? Because we can’t stop wanting what everyone else has regardless of utility. The corporation specializes in turning us into a horde of insatiable wanters. Our ever-expanding get lists, which dwarf our bucket lists, are as unobtainable as the fugitive happiness that getting promises. We want to earn more because we want more, as if happiness is an order or quantity to be filled out.

From our earliest years we are encouraged and then rewarded for being a coin clink in the chain of consumption. There once was a time when respect and status were conferred on those who could save and store. Today, those same rewards are accorded to the devotees of consumption. It’s not the guy with a 15-year-old car but a new car that gets the woman, just as every young man knows or learns the hard way that women are attracted to mega-consumers.

Proportionate to our growing appetite to consume is our contempt for the natural rate of product degradation. Clothes that would normally last five years are chucked after six months. The typical Canadian consumer ditches 680 pounds of textiles per year, 85% of it clothing. We can’t wait to replace our cars, computers and digital devices because marketing experts convince us we are unhappy or unsatisfied with the older versions.

We shouldn’t be surprised that in the 1930s — ironically during the Great Depression — the then already morally suspect corporation introduced the notion of built-in obsolescence, the deliberate producing or manufacturing of inferior products in order to shorten the interval between product purchase and replacement. Following the example of the fashion industry, car manufacturers began to radically redesign their fleets from year to year in order to persuade the consumer that he would be happier with the newer, hipper version. The term throw away culture became current in the 1950s, referring to disposable tableware (mostly plastic) and packaging. Eighty billion pairs of chopsticks are thrown out annually. In 1969, in his seminal The Waste Makers, Vance Packard exposed “the systematic attempt of business to make us wasteful, debt-ridden, permanently discontented individuals.”

Without overstating the case, scientists and environmentalists warn that if we don’t reverse the consumption paradigm, the earth will be unrecognizable in the not so distant future. Every known environment suffers from varying degrees of toxicity because our ability to think for ourselves — wean ourselves from consumption dependency — has been co-opted, hi-jacked, vitiated by the corporation. Our unregenerate thoughtlessness – the necessary invariable in any corporation’s success indices — is the great enabler. The corporation pulls the strings, calls the shots. We are the pawns, the foot soldiers doing the bottom line’s bidding. We have traded away – not a kingdom – the earth for a horse. In The Closing of the American Mind, Allan Bloom writes: “The thoughtless are always going to be prisoners of other people’s thoughts.”

Once it takes root in the mind, it is very difficult to extirpate the greed bug. Microsoft, a multi-billion dollar company whose value exceeds that of many individual countries, without any outside consultation or regard for the well-being of the planet, during the past two decades has – on the flimsiest of pretexts — suspended support for Windows 2000, then Windows XP, then Windows 7, forcing hundreds of millions of users to change their operating system, 95% of whom were happy with their software. The truth of Bill Gates is that while he is giving away millions of dollars to fight malaria and other worthy causes, he is already planning to replace Windows 10, and millions of us will have to retire a product that would otherwise last a lifetime.

Giving Up Cows And Cars

But it is still not too late to reverse current trends and regain control of our critical faculties provided we begin to question our most basic assumptions about life and what constitutes happiness. As more and more of us fall ill from over-consumption as a consequence of envy, depression, obesity, dysphoria, isolation (in the West, 50% of adults now live alone), some of us – the stricken and the damned — will begin to question the virtues of consumption and its dubious promises.

How is it that the wealth of nations is not an indicator of happiness but of production and consumption? Why is growth not a measure of becoming wise but an increase in the value of goods and services? Why are markets more concerned with GDP and not the unit number of pesticides and herbicides and PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyl) found in the food chain? To whom do our eyes belong when they behold the jaundice coloured pall that hangs over every major city in the world if all we do is check into another mall and make another purchase on our debit cards?

Corporations spend billions of advertising dollars (supplied by us, the consumer), to get us interested in products we don’t need, and to get rid of things that are still useful. The corporation understands that if the masses were to be suddenly stricken by the equivalent of a preservation virus, it would collapse, and with it, the entire world order that is responsible for the world’s present peril.

The challenge then is to convince the consumer that in order to save the planet and himself from extinction, he must begin to honour the products he consumes by allowing them to assume their natural rate of degradation, which just happens to be a priceless undertaking everyone can afford.

However unrealistic or idealistic it must seem imagining a world order based not on consumption but preservation, it is not a world unknown to us. From man’s early history until the Industrial Revolution, saving — providing for the future — was prized above everything else. Man, in order to survive, had to learn how to make last the hides that he wore on his back, to preserve and store food supplies to get him through inclement weather, crop failure and political upheaval. His utensils, hunting and farming implements were especially valuable. The tribe, and later the village earned their fitness by learning to Save and Preserve, injunctions informally spoken of as the S & P, an ancient index that commanded universal respect until it was co-opted by finance.

Once the nations of the world find the will to prioritize the launching and dissemination of a coordinated series of S & P initiatives, a new world order will become a reality, and with it, a new configuration of winners and losers. Among the big losers will be corporations in the manufacturing sector as product demand crashes. Industries based on preservation of land and water will thrive as will the health sector and research and development. Industrial and agricultural pollution, over time, will cease to be a major problem; life expectancy will increase, and there will be exponentially fewer children whose IQs are adversely affected by air-borne pollutants and contaminated water.

But none of this is likely to come about in the absence of a catastrophic event. Man will continue on his present perilous course until Venice and other cities go under water, or tens of thousands of city dwellers are poisoned by toxic air trapped in by weather inversions. Meteorological studies single out Delhi, Beijing, Cairo, Varanasi and Mexico City as likely candidates, and if and when it happens it will be irreversible, and thousands of people might lose their lives in a matter of days. In the weeks that follow, the tragedy will be compounded due to lack of facilities to dispose of the decomposing bodies.

If we still can’t see the writing on the wall, are these fatalistic futuristic scenarios — the wake up calls that finally incite us to action — our best hope since it is self-evident that we are unable to command ourselves to act pre-emptively, to do what we know is right?

Man is his own worst enemy, and if he continues to refuse to make peace with the flawed species he sees when he looks into the cracked mirror, his home – The Earth — will soon be another casualty of the war he is waging against his intractable nature.

Left to his own inadequate devices, man reveals himself as incurably inclined to see what “he wants to see and disregards the rest” – a state of mind that portends increasing unrest in a restive world.