For many of us, Rotten Tomatoes is our go-to when deciding whether or not to see a particular movie. As a frequent and shameless user myself, I recently looked up the Joker to see if my own estimation of the film jived with what people were saying. And I discovered something strange.

As of today, Joker holds an 89% rating on RT, which pretty much reflects my own opinion of the film. But that’s just the audience score. Next to that is the critic consensus, which carries a dismal meta-rating of 68%—a 21% difference.

By itself, such a wide discrepancy between audience and critics is not unusual; critics tend to score artistically unoriginal films lower, while viewers typically base their judgment on sheer entertainment value. Basically, critics are more cerebral, while viewers are more visceral. Take, for instance, the first installment of The Fast and The Furious. It received a flopping 53% critic score, but still earned itself a respectable 74% from audiences, also a 21% difference.

So what gives here? For a film like Joker to earn the same critic-audience split as The Fast and The Furious, either Rotten Tomatoes is badly broken or something else is at play. Thankfully, it turns out to be the latter (rest easy, Rotten Tomatoes user).

Social Responsibility Versus Professional Responsibility

Even before Joker premiered in October, fears of copycat violence were widespread. Well-intentioned critics, whose sense of social responsibility outweighed their sense of professional responsibility, had already made up their minds: they would not endorse this kind of movie.

But maybe the movie just isn’t that good? Consider that when Joker first premiered at the Venice International Film Festival, it received an eight-minute standing ovation and took home first prize—enough said. What we are left with, then, is a general sense of fear and uncertainty amongst critics: What am I saying if I endorse this film? What will happen? Will I be responsible if something does happen?

This reluctance is rooted in an understandable desire to keep one’s hands clean in the event of copycat violence—a self-protective measure more than anything else. In fact, I’m not even sure what else the motive could be. Do critics need to feel comfortable endorsing the main character’s behaviour before endorsing the film as a whole? Have these two things somehow become one?

Or is a bad review actually a strategic move? A sort of preemptive strike to deter people from watching the film, one of whom might be the next sleeper-cell shooter, just waiting to have their hazy ideologies clarified by Joker’s descent into madness.

But perhaps, more than anything else, bad reviews are simply a show of solidarity.

The Original Copycat—Debunked

In 2012, James Holmes walked into a Century 16 theatre in Aurora, Colorado and opened fire on a crowd of moviegoers. In the densely packed cinema, Holmes killed 12 and injured more than 70 others.

It was the debut screening of Christoper Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises.

At a Manhattan press conference following the shooting, the now former New York police commissioner Ray Kelly told reporters, “He had his hair painted red, he said he was ‘the Joker,’ obviously the ‘enemy’ of Batman.” Once the press got hold of that story, it spread like wildfire, immediately going viral. You couldn’t invent a more perfect narrative to explain the tragic incident. And so began the undying line that has come back to haunt 2019’s Joker.

But that’s the trouble with good stories—they’re often not true.

Shortly after Kelly’s press conference, Colorado district attorney George Brauchler publicly stated, “It never happened.” Regarding the persistence of the rumor, Brauchler added, “Of course the crazy-hair-colored guy who shot up the Batman premiere thought he was the Joker, of course! And yet it has no connection to reality.”

Dr. William Reid, the psychiatrist tasked with evaluating Holmes’ mental health during the trial, said, “When I asked Holmes about him dying his hair red, he said, ‘Well, my friend dyed his blue, so I said I’d dye mine too and I just picked red.’” As if that weren’t enough to dispel the copycat theory, Dr. Reid went on to say, “[Holmes] said that the first he heard of the Joker idea was [from] somebody in another cell. He heard calling back and forth, ‘Hey, you’re the Joker,’ or something like that.”

Dr. Reid, who later published a book on the subject entitled, A Dark Night in Aurora, explains how Holmes simply chose this particular film screening because it was almost certain to be packed full of people: “He was just looking for a blockbuster, right? Had this been Jurassic World, he’d have been there. Had it been Avengers: Endgame, he’d have been there. He picked that movie simply because it was guaranteed to be full.”

And yet the myth persists, and solidarity follows.

Strap Ideas to Your Chest & Load Your Pistols with Words

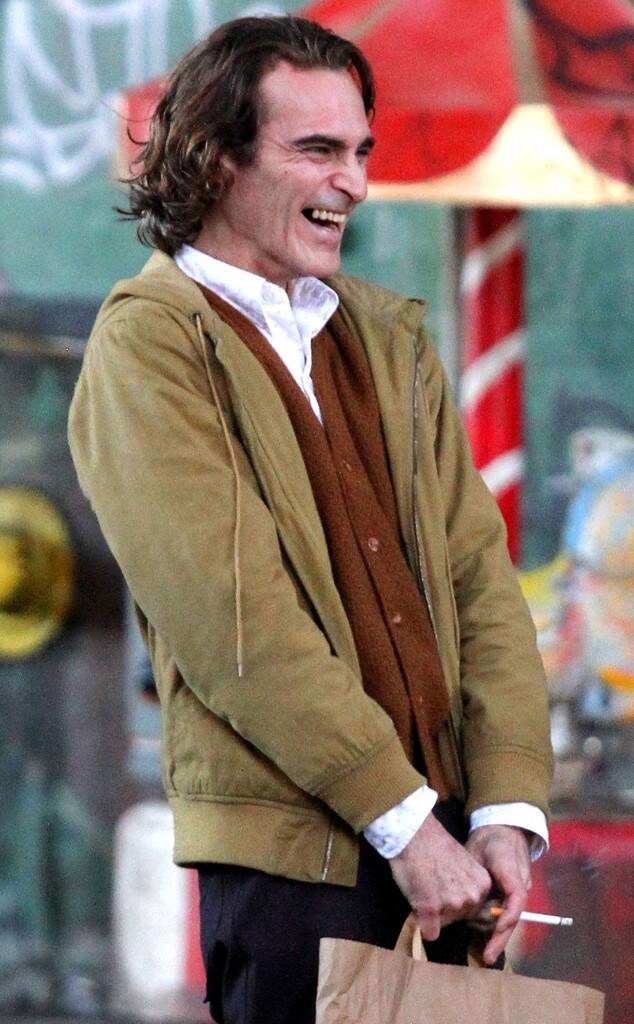

In a recent interview with Joaquin Phoenix, Popcorn host Peter Travers asked, “Is this movie too violent? Can it make other people violent?” To which Joaquin replied, “According to my research, talking about it is irresponsible […]. There was a vast increase in these particular types of crimes after 1963. And that year, there started an unprecedented amount of news coverage about these crimes. And so, people that commit these crimes—this personality type—they seek personal notoriety, they seek personal recognition. That is what they thrive on.”

Regarding the film’s media controversy, Phoenix added, “I don’t think that that’s helpful, and I understand people feel like they’re being the responsible ones, but I don’t think that’s true. And I think the evidence is to the contrary.”

He concluded by saying, “I don’t think movies influence people that way. I don’t think they cause homicidal ideation […]. The conversation around them can be dangerous.”

Similarly, when Marilyn Manson appeared on The O’Reilly Factor, Bill O’Reilly confronted the artist, challenging him about his possible influence leading up to the Columbine massacre. O’Reilly wondered whether it was possible that “disturbed kids” might interpret his lyrics to mean, “when I’m dead everybody’s going to know me.” To this, Manson responded:

Well, I think that’s a very valid point and I think that it’s a reflection of, not necessarily this programme but of television in general, that if you die and enough people are watching you become a martyr, you become a hero, you become well-known. So when you have these things like Columbine, and you have these kids who are angry and they have something to say and no one’s listening, the media sends a message that says if you do something loud enough and it gets our attention then you will be famous for it. Those kids ended up on the cover of Time magazine twice, the media gave them exactly what they wanted. That’s why I never did any interviews around that time when I was being blamed for it because I didn’t want to contribute to something that I found to be reprehensible.

This flips the discussion on its head: Could talking about the potential ‘danger’ the film (or Manson’s music) poses actually be the real danger? Could it be the lust for fame and recognition and martyrdom, and not a simple case of monkey-see-monkey-do, that inspires these acts of violence? Are all those well-meaning critics unwittingly contributing to the potential for copycats?

Blame the Video Games (It’s Easier!)

For those old enough to remember the Columbine shooting, the media’s reaction to the Holmes incident was an eerie deja-vu. Simply swap Marilyn Manson’s music for Ledger’s Joker and presto! you’ve got yourself a motive. Right?

Wrong.

In the aftermath of such horrible events, it’s only natural to look for reasons, to search for the why behind the what. It’s symptomatic of our need to restore order where there has been chaos. If we can elucidate the complex personalities of these mentally unstable killers; if we can find the root cause for their destructive ambitions; if we can pin it on something real and tangible and blame-able in the world—then maybe we can prevent it from happening again.

We are quick to sacrifice nuance at the feet of closure. When it comes to trying to understand something so foreign and disturbing, we prefer black-and-white explanations. Scapegoats like angry music, violent video games and, now, gritty dramas provide us with all the fodder necessary, even though classic studies like Bandura’s Bobo Doll experiment have been discredited.

What’s baffling is that most days we can hardly understand ourselves: Why did I just do/say that? Why am I acting like this? Why can’t I sleep? Why can’t I be happy? And yet, we so easily dismiss mass shooters as nothing more than the product of violent entertainment. How foolish can we be?

Of course, the alternative—to admit that it’s impossible to ever really know someone else’s mind—is an express train to existential angst. Unfortunately, that may be the only viable option we have. Unless we can learn to confront the complexity of human psychology head on, our understanding will never mature past hard-and-fast fallacies.

For now, perhaps the best place to start is by simply treating a movie as a movie.