In January of 1998, Canada had what’s considered to be one of our worst natural disasters to date: an ice storm, resulting in over 100 millimetres of freezing rain and ice showering large parts of Quebec, eastern Ontario, and pieces of the Maritimes. In Quebec, it was referred to as the “storm of the century”, and rightfully so. Public Safety Canada’s disaster database says that 35 Canadians died as a result of the storm, and over 1000 were injured.

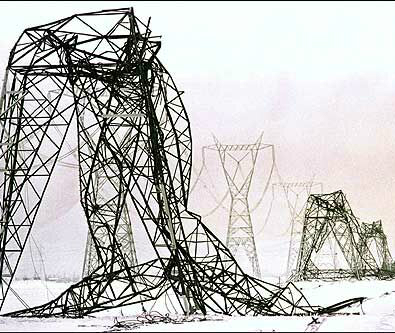

As layer upon layer of sleet blanketed the province, the weight snapped branches off trees, causing the limbs to come crashing down on powerlines. Hydro Quebec’s towers, previously thought to be indestructible given their ability to withstand up to 45mm of ice accumulation, buckled under the weight.

In Quebec alone, 3.5 million people were without power, and many for several weeks. The projected cost in the aftermath of the storm estimated between one and three billion dollars.

If you grew up in Lower Mainland B.C., like I did, you may never have heard of this ice storm. In fact, if you’ve never spent a winter outside of the Lower Mainland (like I hadn’t, up until this last one), then you also might not even know that rain can freeze. Friends back home, you don’t know the half of it.

There’s something to be said about how places form people – the geography we’re raised in is arguably where we learn to thrive, right?

Which is why I have no problem admitting to you that I had a difficult time becoming accustomed to a Quebec winter (one that I’ve been told by many was really not that bad). But the extent of which we are truly formed by our surroundings, particularly when we’re still in the womb, has been something of great interest to Dr. Suzanne King, a Montreal-based researcher, for decades.

When the ice storms of 1998 took place, Dr. King had already been curious about prenatal maternal stress. After the storms, she turned her curiosity into a study on how that stress impacts a child’s health.

The study, titled (arguably the coolest name ever) Project Ice Storm, was (and is) conducted by scientists from the Douglas Mental Health University Institute and McGill University, and started by addressing the maternal personality factors of 178 women who had been exposed to the storms, who either were pregnant at the time, or became pregnant soon after. Researchers also factored in the amount of days without power each woman went through, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and physiological reactions.

Follow-ups with the children born from these women happened every year or every other year, though it’s clear that the follow-up is ongoing, as the goal of the study as it currently stands is “to understand the long-term effects of the prenatal exposure to stress… by studying developmental trajectories through early adulthood,” according to the Project Ice Storm page on McGill’s website.

Through Project Ice Storm, scientists found that women who were in the first half of their pregnancies during the worst of the storms had babies with lower birth weights; pregnant women who were in their third trimester had babies with lower fine motor skills.

In 2014, researchers for Project Ice Storm made a genuine breakthrough, the results of which were published online by Plos One; DNA within the T cells of 36 of these children showed distinctive patterns – an “epigenetic signature” – in DNA methylation (the process by which methyl groups are added to the DNA molecule, which can modify the function of the gene).

What this meant is that, for the first time ever, researchers were able to conclude that maternal hardship predicted the degree of methylation (modification) of DNA in the T cells, a type of cell found in the immune system, and that the objective stressor (the days each woman went without power) was the long-lasting influencer on these changes, not the degree of emotional stress.

The changes in T cells specifically, or in any genes related to immunity and sugar metabolism, put a person at a greater risk for developing asthma, diabetes, or obesity later in life. In June of 2014, Project Ice Storm had results published in both BioMed Research International and Psychiatry Research highlighting the links between prenatal maternal stress and the development of not only asthma, but autism in the children.

And curiously enough, all of the children participants were found to be more prone for anxiety and depression, starting at an age as young as 4.

Researchers for Project Ice Storm acknowledge that the results need to be replicated, and with a larger testing pool, but this is tricky for a variety of reasons.

Moshe Szyf, a McGill University pharmacology and therapeutics professor, and one of the researchers on the project, told the CBC that, though there was previous evidence found that stressing animals during pregnancy had long-term effects in DNA programming and health, it’s obviously unethical to intentionally stress babies. I’d argue it’s pretty unethical either way, but that’s a story for another day.

The fetus is obviously sensitive to the mother’s environment, but what are we to do with that information? It can be a difficult challenge just to maintain stress levels in everyday life, but you add an unborn baby to the picture (or your womb), with a ticking clock as to when that unborn baby will become a screaming, crying baby (entirely your responsibility in every way), and then someone tells you to relax? Have you met a pregnant person?

But on top of all that, now we learn that it’s the actual hardship the mother goes through that impacts the fetus, not her stress levels.

Pregnant women, have you managed to calm down? Excellent, now go find someplace peaceful, serene, and immune to any kind of natural disaster.

To date, nearly 100 families are still participating in Project Ice Storm while researchers “continue to analyze the rich data collected over the years,” though their page also states there are currently no new assessments planned.