We choose to go to the moon, not because it is easy, but because it is profitable…

As Elon Musk’s has just completed SpaceX first commercial launch and Jeff Bezo’s Blue Origin and Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic trailing not so far behind, the billionaire space race seems to have solidified itself as the future of space travel. The incredible strides that these companies have made in recent years has created a world where it is more than likely that the first rockets to reach Mars will be decorated in corporate bumper stickers.

But how did this happen? How did an industry that was once so symbolically tied to the effectiveness and greatness of the government that it represented become the domain of high-flying billionaires with lofty ambitions?

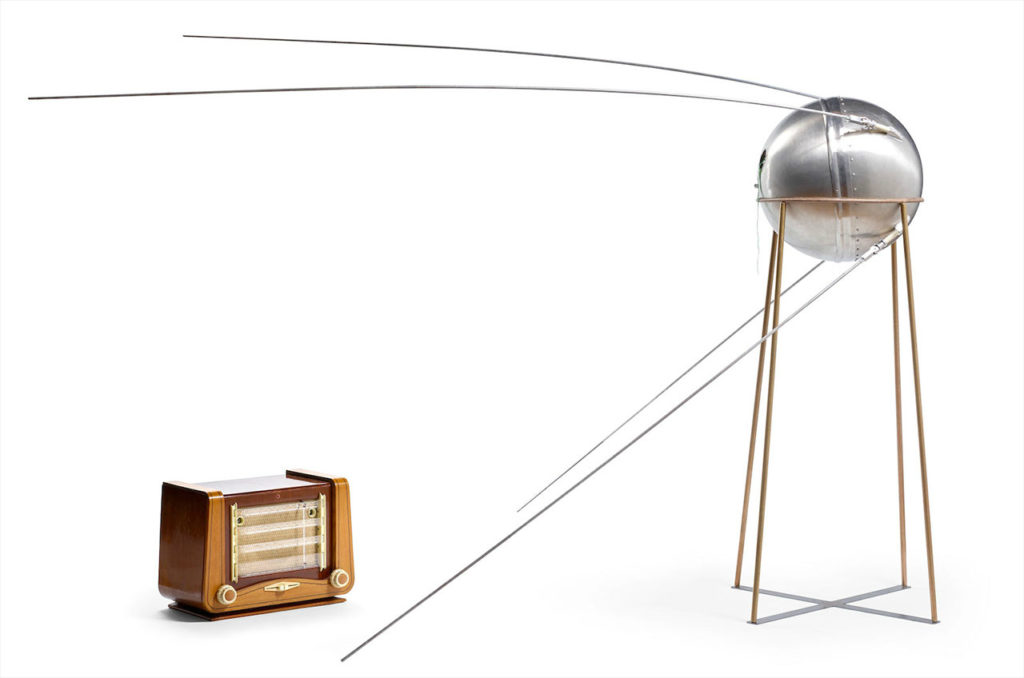

Contrary to popular belief, modern space travel didn’t start so much as an optimistic urge to boldly go where no man had gone before, but instead as a paranoia-driven obligation to do so. On Oct. 4, 1957, the Soviet Space Program launched the Sputnik 1 Sattelite into an elliptical low Earth orbit. While the satellite did little more than beep, Sputnik 1 conjured up images in Cold War America’s head of communist A-bombs dropping down on them from the skies up above.

Sputnik 1 sent a clear message to the Americans, and the space race quickly became an out-in-out grudge match between Communism and Capitalism. The finish line was clear: landing a man on the moon. And both superpowers raced toward that finish line with everything they had.

Of course, the rest is history.

The Americans won the space race without question with Apollo 11 successfully landing on the moon in 1969. However, by the time that Neil Armstrong finally made his great leap for mankind, NASA had burnt through close to $23 billion dollars (over $100 billion today) of taxpayer money.

And while landing a man on the moon quickly became a benchmark of scientific achievement and one of the most important cultural moments in American history, it was not without criticisms. Going widely over budget and experiencing devastating setbacks–multiple astronaut deaths and millions of dollars wasted in malfunctions– even the cold warriors of 1960s America started to see past the Communist threat and ask themselves “is going to the moon really worth it?”

Once America had secured its spot as the world leaders in space exploration that sentiment became more and more concrete with few people even realising that the Apollo program sent a total of 10 astronauts to the moon following the initial Apollo 11 success.

This disconnect that grew between Nasa’s lust for more astronomical adventures and the economic realities of the time opened a gap in the marketplace that the private sector quickly filled. By 1981, NASA had developed new ways for the space program to pay its own way into space.

The Columbia spacecraft was NASA’s answer. Unlike its predecessors, Columbia was touted as the first reusable spacecraft. Instead of using a single rocket, Columbia would launch itself into space using an external fuel tank and two solid rocket boosters. After achieving orbit the shuttle would then return to Earth as a plane and land safely on a tarmac.

While, for obvious reasons, this new style of space travel cut costs dramatically, the shuttle also managed to market itself as an interstellar courier company. Along with its astronauts, Columbia would also carry important payloads for private contractors and other government agencies, like the Department of Defense, into orbit.

It seemed like the perfect solution to keep the scientific explorations that had once captured the American imagination so entirely alive.

But with the new cash injection from the private sector, NASA was no longer solely focused on chasing the dreams that space exploration once promised. Now, they were also focused on chasing the bottom line.

NASA had its eyes focused on launching 60 shuttles a year, and, with that, becoming a completely self-paying space program. With the benefit of hindsight, most experts would agree that this goal was completely fantastical. However, the political and economic pressures of the time were very real. NASA put its team of engineers under incredible scrutiny to find the most cost-effective ways to have rockets shooting up into space almost every other day.

And that pressure; ultimately, led to tragedy.

By the 10th Challenger launch on January 28, 1986, the realities of NASA’s incredibly ambitious time schedule finally caught up to them. Despite the urgings from chief engineers to push back the timeline of the launch due to concerns over a possible o-ring malfunction, NASA continued with the launch as planned. An estimated 17 percent of Americans witnessed the deaths of Francis R. Scobee, Michael J. Smith, Ronald McNair, Ellison Onizuka, Judith Resnik, Gregory Jarvis, and Christa McAuliffe on live television.

The victims were far and away from being the first astronauts to die aboard a space shuttle; however, the Challenger explosion along with the Columbia Space Shuttle disaster in February of 2003 led to serious overhauls in NASA as an organization.

The two tragedies created mountains of bad press and, despite their best efforts, the organization was never truly able to balance its budget. The result was that NASA shifted it’s focus to smaller un-manned spacecrafts and began allocating it’s more ambitious projects to separate entities.

The bulk of American astronauts launched into space over the last two decades have done so from a Russian launch site, and, since the early 2000s, private companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Virgin Galactic have been sweeping up more and more government Commercial Resupply contracts.

Although this shift might feel like the end of NASA, it is far and away the death of public interest in space exploration. In fact, many feel that the involvement of celebrity billionaires in an industry once gatekept by nation states has rekindled the inescapable curiosity that people all over the world first felt when Apollo 11 landed on the moon.

The new space race is about more than just government contracts. These industrious few have dreamt up a future of space tourism where even regular Americans can travel the solar system. And this isn’t a pipe dream. Since the year 2000, venture capitalists have put roughly $13.3 billion into space projects. Why? Because they truly believe that they are witnessing the birth of a multi-trillion dollar market.

Elon Musk, Richard Branson, and Jeff Bezos have done more than bring a little mainstream appeal to an industry that, for so many years, has been restricted to an esoteric cult of space nerds. They’ve also brought technological advances.

In December of 2015, SpaceX achieved the first propulsive landing of an orbital rocket and has since proven the technology with 20 successful launches last year and 18 the year before that. Bezos’ Blue Origin has also made headlines by creating a new engine for the United Launch Alliance, and having an active lunar landing program. And, despite a tragic crash in 2014, Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo reached the lower edge of suborbital space last December.

Sources:

https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2018/10/18/the-space-race-is-dominated-by-new-contenders

https://www.economist.com/leaders/2018/01/18/the-new-space-race

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elon_Musk#SpaceX

https://www.space.com/spacex-falcon-heavy-arabsat6a-april-2019.html

https://spacenews.com/blue-origin-still-holding-off-on-new-shepard-ticket-sales/

http://www.historyshotsinfoart.com/space/backstory.cfm

https://www.thebalance.com/nasa-budget-current-funding-and-history-3306321

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-O_DMyHdq_M

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NASA#Space_Shuttle_program_(1972%E2%80%932011)